Garden Cities – Suburbs, back to the future…

Christopher, in the comments of my post on the American Dream, mentioned this great photo gallery over on Slate from Witold Rybczynski of Forest Hills Gardens, an American interpretation of the Garden Cities of the turn of the century. Chris notes these Garden City suburbs have all of the principles of today’s New Urbanist communities – transit orientation, sufficient density, mixed uses and mixed incomes, etc.

It’s all about access

Cap’n Transit continues on his campaign for transportation to focus on accessibility over mobility. The two concepts, of course, are intricately related, but accessibility is the more important paradigm for urbanism and city life:

Last week Grist had a well-sourced article (which came to me via Planetizen, via Portland Transport, via Streetsblog.net) that nicely illustrates how improving access without mobility can get people to drive less. And of course by driving less, we reduce pollution and global warming, increase energy efficiency, and all the rest. In this case, when stores are located within walking distance, people walk more, improving their health as well.

Transportation planners should be willing to acknowledge when there’s a possible non-transportation solution that’s worth considering, especially when they’re dealing with taxpayer money. They should then be prepared to say, “You know, you really need a business development planner. That’s not my specialty, but let me introduce you to Joe, who’s really good at fostering downtown businesses.”

This kind of integration between professional disciplines ought to be the goal. Of course, that’s easier said than done. Nevertheless, fostering regulatory environments where such holistic understandings of urbanism, transportation, and the interconnections between them ought to be encouraged.

At the same time, I don’t think we need a complete revamp of the current system – but encouraging these conversations and spreading these concepts amongst the population at large is important for planners and urbanists.

Great Station Architecture

Aaron Renn has a post on the potential of Chicago’s El and other transit systems to be not just good, but great. At the end of the post, Renn has a great collection of photos from various transit systems around the world – showing off great station architecture and high-minded design. The gallery is well worth a look.

Within that discussion, Matt Johnson has a fantastic set of posts at GGW on the basic design elements of Metro’s system (part one – underground stations; part two – above-ground stations; part three – other motifs). Matt lays out the basic elements of Metro’s stations and how they’re both constant yet varied within the system.

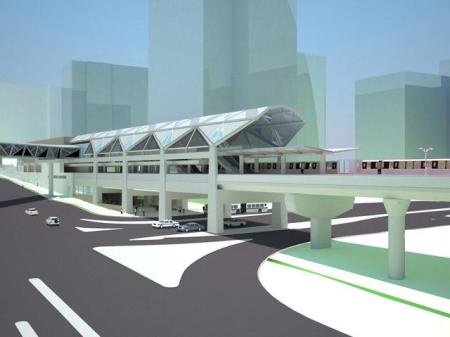

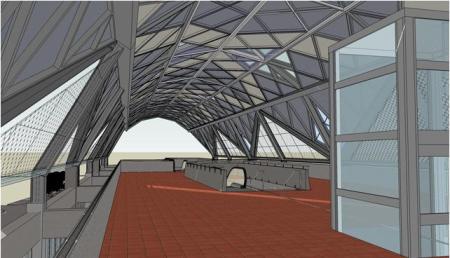

When it comes to creating great stations, DC’s immediate opportunity will be on the Silver line. Discussion in the comments asked about the sole underground station on the new line (at Dulles), but since that station is in the second phase of construction, we don’t have renderings of the architecture – just some basic engineering. We do have, however, renderings from the stations in phase one – and the comments in part two of GGW’s thread weren’t exactly complimentary of the architecture.

Some photos from the Dulles Metro website:

Tysons Central 123

Tysons Central 7 – interior

Tysons East

In other station news – over in Vienna, Jarrett Walker has a post on station architecture there – focusing on the Art Noveau elements.

While we’re in Vienna…

Jarrett also has some posts on other elements of Vienna’s transit systems.

First, he has a follow up on the city’s overhead wires. Jarrett’s great photos allow the reader to decide if those wires ruin the city or not. My opinion is that they do not, and they won’t mean the end of the world for DC, either. That is, once we decide to bring our new streetcars back from the Czech Republic.

Jarrett also notes about the excellent network effects within Vienna’s system – including cross-platform transfers. Making transfers easy is an important part of a great system – even in DC, plenty of people I know hate to switch lines, especially at off-peak hours when trains run more infrequently. Jarrett notes:

In talking about transit planning I’m constantly stressing the need to think in terms of interconnected two-dimensional networks, not just the one-dimensional “corridors” that are the focus of so many transit studies. It’s a hard point to convey because (a) interconnectedness implies connections, also called “transfers,” which people supposedly hate, and (b) networks are complicated and abstract and hard to think about, which is why I’m always trying to create and promote tools for making them simpler.

What’s more, network effects are really hard to photograph. The closest you can come is a photo of a really smooth cross-platform connection.

A cross platform transfer allows a rider to switch lines by simply crossing the platform to a different train without having to switch levels, as you currently have to do at Metro Center or the other main DC transfer points. This diagram from Wikipedia shows how a cross-platform transfer works in Hong Kong’s MTR:

Basically, the train lines weave for you – thus the passenger does not have to navigate stairs/escalators to get to a different platform to switch lines. Each train stops twice in this one ‘station’ – one stop facilitating a transfer to the other outbound line, the second to the other inbound line.

Basically, the train lines weave for you – thus the passenger does not have to navigate stairs/escalators to get to a different platform to switch lines. Each train stops twice in this one ‘station’ – one stop facilitating a transfer to the other outbound line, the second to the other inbound line.

Jarrett also references one of his other posts, where he notes why transfers are good and why we should try to make them easy – they really make the system as a whole function smoothly.