Streetcars

We’ve got more details on DC’s streetcar plans. BeyondDC has more details on the plans (at BDC/GGW), and Yonah Freemark chimes in with comments at the transport politic.

And, just for fun, this is a great reason to link to the old map of DC’s streetcar system circa 1958 (matching many of DDOT’s historical photos).

Metro Extensions

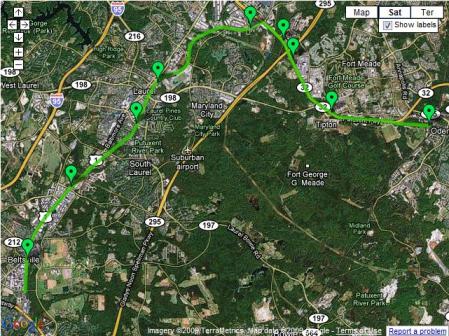

In other transit expansion news, Prince George’s County is working on re-doing their transportation plan. One of the ideas thrown out so far is an extension of the Green Line from Greenbelt through to Laurel:

The county also wants the Green Line extended from Greenbelt to Fort Meade by way of Beltsville and Laurel. The stops could include Konterra, a massive mixed-use development underway at the eastern end of the ICC.

GGW’s summary on these developments also links back to previous posts on the plan’s highway and transit components. Dave Murphy, however, takes the Green Line extension idea and improves upon it – by diverting the Metro extension away from the CSX/MARC Camden line tracks though Fort Meade (which is already a huge employment center and set to grow even more with various BRAC relocations) before terminating at Odenton – also connecting with the MARC Penn Line.

The idea of serving Fort Meade is good – it needs more transit service to meet growing demand. Likewise, the idea of connecting both MARC lines together through Fort Meade is also good. The problem, however, is that Metro isn’t the best tool to accomplish this task. It’s the most expensive mode of transit we have in this region – and should be reserved for the highest capacity, highest potential routes.

The desire to extend Metro rather than invest in other modes is understandable – everyone wants the best. However, in this case, a massive upgrade of MARC service would be more appropriate and cost-effective – expanding service days and hours, increasing frequencies, offering through-routing to Virginia, and so on. This site has the advantage of MARC lines on both sides. If service levels could be increased to match those on some of the Metro-North commuter lines (10-20 minute peak hour headways, late night service, weekend service), extending the Metro wouldn’t be needed. In the comments of the GGW article, BeyondDC provides an alternate proposal – increasing MARC service while building a cross-“town” light rail line to provide service through Fort Meade.

These kinds of ideas, whether they’re fantasy maps or some other proposal, always generate a lot of interest. Matt Yglesias offers his thoughts:

Here I think the key thing to keep in mind is that when you’re talking about new heavy rail construction, the potential benefits can be quite large but you have to decide if you actually want to seize them.

If you added a Metro station there, would the local area permit the surrounding quarter mile or so developed as a fairly dense walkable community? Or would people hear about proposals to build on the green space and up-zone the built-up area and decide that would lead to too much traffic? Maybe instead they’ll want to just turn the undeveloped patch into another parking lot. That’d be no good. And the existing land use patterns around Maryland’s Green Line stations don’t inspire a ton of confidence.

Of course, it’s much easier to create an urban environment in an urban setting – plus, you can create the same kind of TOD/urbanism with a heavily accentuated MARC service.

Ryan Avent also chimes in at The Bellows:

To expand on this a little bit, Metro is the region’s most expensive transit option, but it’s also the one with the greatest potential to drive development. Generally speaking, we want to plan our transit systems so that we’re maximizing the benefits we get for the cost of the investment. If Maryland isn’t prepared to zone for significant development around Metro stations, it would be very silly to make the large investment in Metro. Better to develop a commuter rail line or light rail line or both (depending on anticipated development and commuting patterns).

Metro can indeed help shape development, but it’s important to realize that Laurel is still Laurel – no matter how you slice it, it’s a long ways away from downtown DC.

The Silver Line, to take another example, is an expensive investment. It would probably have been much smarter to simply connect Fairfax County destinations (and Dulles) with Arlington and the District via commuter rail but for the fact that the new Metro line is part of a major effort to increase density at Tysons corner.

The key difference between a Green line extension and the Silver line, however, is that the Green line already parallels an existing transitway with huge potential to upgrade service on the cheap (relatively speaking). The Silver line doesn’t have a similar option – Commuter Rail beyond Tysons Corner would indeed be a great option in the abstract, but the conditions don’t exist to make it work.

Avent’s conclusion is spot on, however. Extending Metro further out along the Green line is a mis-match between location and mode, and these kinds of mis-matches will impose costs on the core. Instead of a Parisian system where the Metro and RER compliment each other, Metro’s hybrid nature pushes these two uses into the same system.

These costs are increasingly borne by users in the core of the system, where growth in the number of trains and passengers have led to crowded conditions on platforms and back-ups during peak periods. To some extent, this can be addressed by increasing peak fares, but given the obvious value of Metro, the growth in the system’s spokes, and the fact that the District is better suited than almost anywhere else in the metro area to handle increased density, it seems clear that new core capacity is needed (as well as a new river crossing over or under the Potomac).

Metro doesn’t stop running when it enters the District. If Virginia and Maryland want to continue to build Metro extensions, they ought to offer their full support to an effort to add capacity in the core.

What’s more – investments in the core (say, in the form of a new, separated Blue line) will bear fruit for lines outside the core as well. The new Blue line would eliminate the capacity constraints of the interlined portion of track through DC – thus increasing the potential capacity on existing Orange and Blue line track in MD and VA.

Georgetown

Georgetown Pennsylvania Ave, looking at the Treasury Building, circa 1925.

Pennsylvania Ave, looking at the Treasury Building, circa 1925. Looking north up Connecticut Ave towards Dupont Circle, 1958. Note the two underpass entrances – the nearest for streetcars and the other (currently extant) for cars.

Looking north up Connecticut Ave towards Dupont Circle, 1958. Note the two underpass entrances – the nearest for streetcars and the other (currently extant) for cars.